My sketch of the learning theoretical field will proceed in three stages. First, I shall take up the characterization of research within the field provided by Sfard in 1998 as basically led by two incommensurable metaphors; the ‘acquisition metaphor’ and the ‘participation metaphor’(Sfard, 1998). Given that these two metaphors involve very different epistemological claims which both appear to be related to what I have been arguing above (albeit not at the same points), and that the aim of this section is to clarify-by-contrast my view of knowledge, a characterization of the field founded on this distinction is in the present context the most basic one to make. Within this field I shall locate my position as a reconciliatory one. Second, because my view has many similarities with – and indeed, within the frame of my Wittgensteinian-cum-phenomenological outset, has been inspired by – the sociocultural tradition stemming from Vygotsky, I give a depiction of how my view relates to this tradition. The focus will be on how sociocultural views on tool use and distributed knowledge relates to my claims about the interrelation of knowledge as an action-oriented perspective and the affordances of phenomena in the world. Third, because my focus throughout the anthology is on the individual (even if on the individual-in-the-world), I take up the question how my position relates to other individualist views. I do this through presenting Illeris’ schematization of the learning field as drawn out between the three dimensions of content, incentive, and interaction. It should be noted that this way of depicting the learning field is (in Sfard’s terminology) fundamentally acquisitionist and construes participationist views on that basis. In consequence, from the participationist standpoint, Illeris’ schematization is somewhat misguided and misses essential insights. My location of my position in the schematization should therefore be understood on the background of the characterization I will by then already have given of the acquisitionist-participationist discrepancy.

Turning now to this discrepancy, Sfard in her 1998 article pinpointed the acquisition metaphor as the one which has traditionally guided research within the fields of learning and education and argued that it is still prevalent in both lay and research conceptions of learning. Central to this metaphor (as also indicated in the discussion above) is the view of knowledge as a ‘something’ and of learning as the process of ‘acquiring’ this ‘something’. The metaphor is a common background assumption of approaches which diverge on more specific questions such as which kind of process acquisition is, which kind of ‘something’ knowledge is and to which extent this ‘something’ has existence and can be specified prior to the acquisition process. Examples of positions which build on this metaphor include cognitive information processing theories (e.g. Anderson, Reder, & Simon, 1996; Mayer, 2001, 2004; Mayer & Massa, 2003), individual constructivist theories (Carey, 2009; Cress & Kimmerle, 2008; Glasersfeld, 1995; Piaget, 1950; von Glasersfeld, 2001), as well as theories emphasizing the importance – or even necessity – of other learners for individual cognitive growth, such as cognitive confrontation theories (e.g. Andriessen, 2006; Andriessen, Baker, & Suthers, 2003; Dillenbourg & Tchounikine, 2007; Jermann & Dillenbourg, 2003; Weinberger, Ertl, Fischer, & Mandl, 2005; Weinberger, Stegmann, Fischer, & Mandl, 2007). Even Vygotskian-inspired socio-constructivist theories fall within this category because their approach to learning as an internalization or appropriation of socially mediated knowledge also delimits a kind of ‘acquisition’ process (e.g. Dawes & Wegerif, 2004; Hedegaard, 1995; Vygotsky, 1978).

In contrast, the participation metaphor, according to Sfard and in concord with my discussion of the situated learning theorists above, expresses a view of learning as changing participation in the activities of a specific community where the goal for the newcomer is to become a ‘full’ member. This focus for learning entails a wider domain for research, because people participate in many communities outside the educational institutions, both at their workplace and as part of their private and societal lives. For instance, Lave and Wenger (1991) analyze Cain’s case of Alcoholics Anonymous (later published in Cain, 1991; cf. also Holland, Lachicotte Jr, Skinner, & Cain, 1998) as a particularly salient example of apprenticeship where newcomers over time learn to tell their life stories in the vein of the old-timers. In the course of the process, they come to see themselves in a new way, namely as non-drinking alcoholics. Likewise, the focus involves a shift in phenomena to be investigated, from knowledge and its development to activities and their negotiation between participants. The objectifying term ‘knowledge’ tends, as Sfard notes, to be absent and to be substituted with the active term ‘knowing’. To the extent that it is used, it is often in the characterization of the ways participants in a given practice themselves delimit the activities they value. As Wenger puts it:

Knowledge is a matter of competence with respect to valued enterprises – such as singing in tune, discovering scientific facts, fixing machines, writing poetry, being convivial, growing up as a boy or a girl, and so forth… Knowing is a matter of participating in the pursuit of such enterprises, that is, of active engagement in the world. (Wenger, 1998, p. 4).

A key point – to the participationists themselves and to the use I have been making of their arguments above – is the situativity of concepts, words and actions: Concepts, words, and actions become meaningful in concrete situations in the process of the participants’ negotiation with each other and with their physical and social surroundings. This negotiation will sometimes take the form of explicit verbal argument, but oftentimes it will be implicit in what participants say and do, as well as in what they do not say and do.

In my presentation above, I have referred to the views which build on the participation metaphor as ‘situated learning theorists’. This terminology is widespread, amongst theorists who count themselves as proponents hereof (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Nielsen, 2013; Nielsen & Kvale, 1999) and more generally (e.g. Anderson et al., 1996; Qvortrup & Wiberg, 2013; Vosniadou, 2007). In other texts, however, participationists are characterized (by themselves and by others) as ‘sociocultural’ (Greeno & van de Sande, 2007; Gresalfi, 2009; Murphy, 2007; Packer, 2001; Packer & Goicoechea, 2000). The reason for the different terms is one of conceptual history: Situated learning is a position (or set of positions) which has evolved within sociocultural theory. The latter term covers a much broader range of positions which originate in the writings of Marx but more specifically in the work of his Soviet theoretical heirs, notably Vygotsky, Bakhtin, Leontiev, and Luria. Thus, sociocultural theory encompasses the positions of Kaptelinin, Nardi, Dysthe, Hedegaard, Klausen and Hutchins (Dysthe, 2001; Dysthe & Engelsen, 2004; Hedegaard, 1995; Hutchins, 1993, 1995; Hutchins & Klausen, 1996; Kaptelinin, 1996; Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2006, 2012); writers who all view learning through the lens of the acquisition metaphor. The term ‘sociocultural’ here indicates the significance which social relations and cultural background, tradition, and history are ascribed: A person is born into cultural practices with a given material ‘base’, including specific tools and technologies for dealing with the world. Sense-making takes its outset in the cultural practices, in that they delimit the overall sense which can possibly be made of objects, humans, relationships etc., as well as supply concrete paradigm instances of sense-making for most situations. The view, as Packer and Goicoechea (2000) stress, has its roots in Hegel’s (and Marx’) interactionist understanding of personhood (cf. above). It is non-dualist and relationalist: Person, activity, and world are dialectically related and mutually constitutive: The person becomes a person – a self – in interaction with others and the world. The world becomes what it is through human practical activity in it. An activity has meaning in a social world where people act and negotiate its significance. As humans we are always already engaged in meaningful activity in a socially structured world and the split between object and subject, present in Cartesian epistemology (cf. above, section 2.1, and below, next section), is derivative and secondary. It involves ‘stepping back’ from the world, objectifying it, and neglecting that the primordial, practical, precognitive engagement in the world is a prerequisite for the ‘stepping back’. When a person enters more specific practices in e.g. schools or professional settings, she as a newcomer is initiated into culturally established traditions which she may participate in the negotiation of to some extent, but which she at some level has to accept and comply to if she is to be acknowledged as part of the practice at all.

It is this general sociocultural claim which for the participationist becomes the focal point for learning – the attunement to conditions of participation, changes over time in these conditions, and corresponding transformation of ways of participating. Whereas the acquisitionist within the sociocultural tradition will focus more on the issue of how the individual comes to master cultural tools and appropriate sense-making practices as her own. Still, some differences exist even between situated learning theorists concerning especially the extent to which learning as participation is seen as initiation into versus transformation of social practice. The differences are due partly to variant foci, with some theorists looking primarily at the development of participation within a given practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Nielsen, 1999; Nielsen & Kvale, 1999; Tanggaard, 2005, 2006; Wenger, 1998) and others focusing on agents traversing different practices and the ways in which such ‘boundary crossing’ (Akkerman & Bakker, 2011) affects their participation in the specific practices concerned (Dreier, 1999a, 1999b, 2003, 2008; Østerlund, 1997).

The view I have been presenting above may be termed ‘sociocultural’ because of the emphasis I have placed on cultural practices and social mediation at the highest analytical levels of situational demands. Nonetheless, the fact that I argue for the context-dependency of social mediation, in particular at the lower analytical levels, makes my position a non-typical sociocultural one to the point of it being more reasonable to speak of it as a ‘practice-grounded’ one (cf. Article 8). I return to the issue of divergences between my view and (other) sociocultural ones below. For now, I concentrate on the overall landscape as defined by the two basic metaphors of learning.

Sfard originally claimed that the metaphors were incommensurable, yet complementary, and that adequate educational research and practice ought to be informed by both (Sfard, 1998). Others have stressed the complementarity of the two basic approaches, even if they have not framed the discussion in terms of metaphors (e.g. Cobb, 1994). Over the years, several attempts have been made to combine or reconciliate them (Billett, 1996; Greeno, 2011; Greeno & Gresalfi, 2008; Greeno & van de Sande, 2007; Murphy, 2007; Sfard, 2008; Vosniadou, 2007). However, there is little accord on more specific suggestions for reconciliation. Greeno and van de Sande thus for example explicitly take their outset in the distributed knowing and interaction in social activity systems and understand learning as construction of perspectival understandings in relation hereto. Sfard has provided a participationist interpretation of math objects as recursive trees of visual realizations in unfolding discourse within math education. Vosniadou on the other hand views participation in sociocultural activities as a means for individual learners to acquire mental models (Vosniadou, 2007). Murphy similarly has a fundamentally acquisitionist view when she focuses on individual learners’ conceptual change, even if she considers sociocultural factors as well as cognitive ones vital for initiating the change (Murphy, 2007).

Agreement is thus only reached at the general level that both aspects of ‘individual acquisition’ and of ‘participation with others’ must be taken into account in theories of learning. But there is a fundamental difference between seeing participation as a means for individual mental construction and seeing the cognitive processes of individuals as aspects of the flux of distributed knowing and interaction. In the first case, knowledge resides solely in the minds of people and the role of interaction is to prompt individual knowledge acquisition. In the second case, the situated knowing of the activity system is an emergent phenomenon in its own right which cannot be reduced to or explained fully by the sum of individual cognitive contributions. It certainly is not just a means for individual knowledge acquisition. From this point of view, the divergence of focus for the analysis of learning (the individual versus the community) and the discrepancy in views on the nature and locus of knowledge have not yet been overcome. Furthermore, these different attempts at reconciliation gloss over what I see as the most important difference between the acquisitionist and the participationist approaches: whether one can adequately discuss and answer questions of knowing without considering the person – as a person; the formation((In the sense of the German Bildung or Danish dannelse, cf. (Brejnrod, 2005; Jank & Meyer, 2005; Klafki, 1963).)) of the person – who knows. Acquisitionist theories answer in the affirmative, participationist theories in the negative. My own stand in this matter is the by now repetitive contention that it will depend on the more specific situation and on the knowledge domain in question, as well as of course on the precise question one is asking. Utilizing the examples of Article 2, it seems unreasonable to claim that a person googling information out of boredom or learning a word in a foreign language he takes no specific interest in – in both situations coming to know facts to which he is somewhat indifferent – is necessarily affected as a person in the process. But in general, if one wishes to understand what goes on in a given situation and especially if one wishes to plan for certain learning opportunities to arise for certain people, it may be necessary to consider how knowing and being intertwine for them and how this intertwinement and the social interaction one expects to occur will mutually influence one another.

A clarification is needed at this point: Saying that the acquisitionist approach does not entail consideration of the knower’s formation as a person does not imply that no one within this approach has reflected on aspects of identity or self or on their significance for acquiring knowledge. On the contrary, studies of the ways in which motivation (Ames, 1992; Ryan & Deci, 2000a, 2000b), self-concept (Jordan, 1981), self-esteem (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003), self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977, 1982, 1993, 1997), learning styles (Kolb, 1984) and various metacognitive strategies (Flavell, 1979; Hacker, Dunlosky, & Graesser, 2009; Paris & Winograd, 1990; Perfect & Schwartz, 2002) affect cognition are all clear examples of acquisitionist positions which relate emotions, personal ‘traits’ and/or ways of self-management to the acquisition of knowledge. Nor do I claim that there is no implicit view of the formation of the person inherent in the acquisitionist approach. As Packer and Goicoechea (2000) show, there are such implicit views, namely, for acquisitionist approaches of the cognitive or constructivist kind, a Cartesian one of the self as self-formed and independent((Martin (2007) has elaborated on this implicit view, arguing that cognitive and metacognitive approaches to learning embody a concept of the ‘managerial self’. )), and – to reiterate – for sociocultural acquisitionist approaches, a Marxian one.

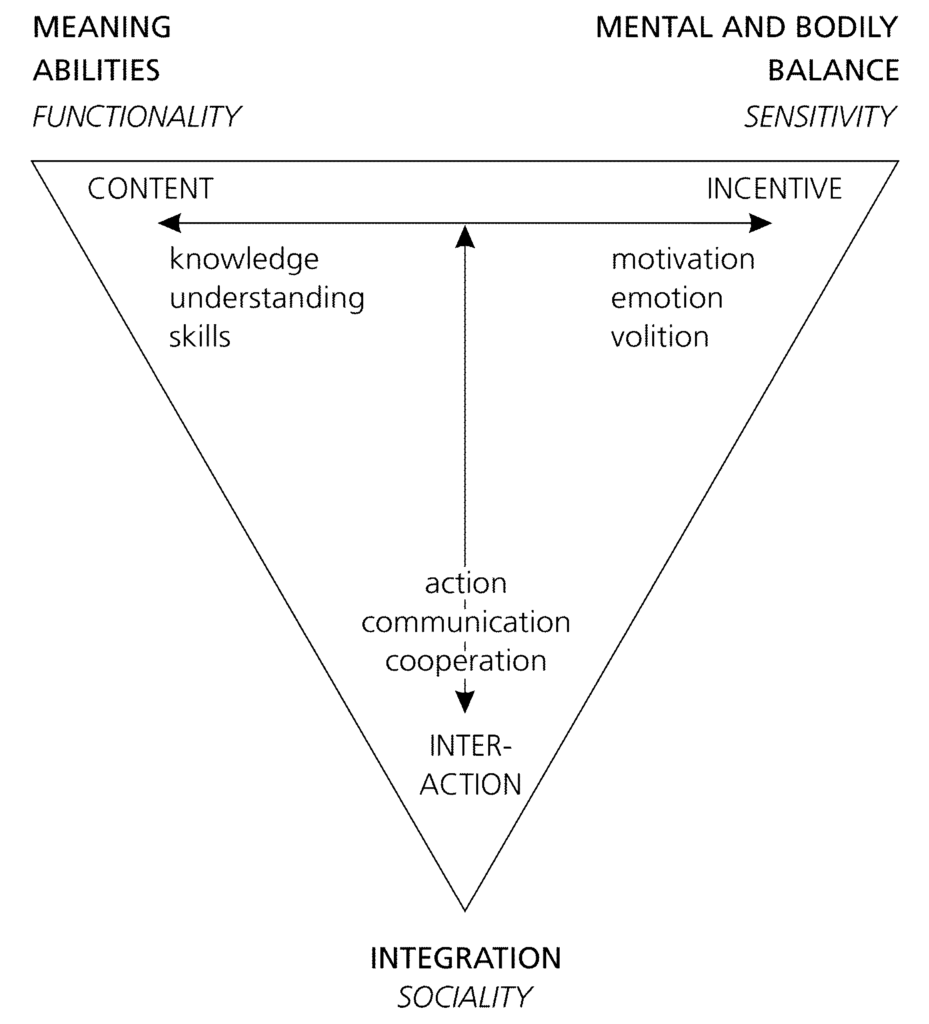

My point is, however, first, that acquisitionists treat cognition as a phenomenon which exists in its own right, in principle independent of other phenomena such as motivation, emotion, dispositions and higher level cognitive factors (metacognition), though in specific situations it may be influenced by such other phenomena. And second, because knowledge acquisition is seen as an in principle independent phenomenon, it is possible to delimit one’s investigation from other phenomena and concentrate solely on this one phenomenon. In other words, acquisitionists may choose to inquire into the significance of other phenomena, but they do not have to. Illeris’ learning triangle (Illeris, 1999, 2007, 2009) is a paradigmatic – and paradigmatically clear – exposition of the acquisitionist view of the relationship between knowledge acquisition and other factors (cf. figure 1): Knowledge, skills, and understanding is viewed as one corner of the triangle, the ‘content’ corner. The second corner, ‘incentive’, encompasses motivation, emotion, and volition. The third corner, ‘interaction’, is claimed to involve action, communication, and cooperation. The triangle is thought to represent three ‘dimensions’ of learning. Two-way arrows indicate that the dimensions influence each other. Different acquisitionists may attach varying degrees of importance to the two other dimensions, but the point is that knowledge acquisition is treated as one dimension, influenced by, but independent from the others.

In contrast, participationists do not consider questions of knowing to be answerable in isolation from questions of who the person is recognized, negotiated, and striving to be. Knowing, being, coming-to-be, participation and negotiation in social interaction are viewed as internally related aspects that cannot be adequately characterized, let alone investigated, on their own. As Greeno has put it: “In the situative perspective, learning and development are viewed as progress along trajectories of participation and growth of identity” (Greeno, 1997, p. 9). In other words, consideration of the knower’s formation as person is not a matter of choice, but a matter of necessity for the participationist, if an epistemologically and ontologically sound account of learning and knowing is to be had, i.e. an account which is not distorted and does not leave out essential aspects.

Within this landscape, my view presents itself as reconciliatory in a way which at the same time somewhat challenges the basic distinction between learning as acquisition and learning as participation. My position originates in an epistemological concern with understanding the individual’s development of ‘knowledge in practice’ as an action-oriented perspective. This is, at heart, an acquisitionist issue. However, as argued previously, the more specific characterization of the perspective which I have given is not compatible with viewing it as an ‘object’, nor can its development be seen as an ‘acquisition’ (though I sometimes use the word) of a ‘something’. Rather, the perspective is a style of being which opens the world to one ontologically and epistemologically. As such, the formation of the person is inherently involved in the process. This signifies a participationist point. However, since no assumptions are made on beforehand as to the degree to which social negotiation of knowledge aspects and person determines the ‘style’, and since, conversely, it is accepted that not everything learned will be learned as an integration into the perspective, my position is not clear-cut participationist, either. Again, the fact that I distinguish between several analytical context levels allows me to take account of points from both theoretical strands, whilst leaving their specific interplay in practice a matter for empirical investigation.

This classification of my own view within the landscape drawn by the acquisitionist-participationist discrepancy leads me to the second stage of my ‘clarification-by-contrast’. At this second stage, I pinpoint the ways in which my understanding of the relationship between knowledge and affordances concurs with and differs from the view found within acquisitionist sociocultural theory of tool use and its significance for the development, exercise and evaluation of knowledge. These questions follow naturally from the preceding classification because the way in which my view is at once reconciliatory between the acquisitionist and participationist strands and challenging of them is precisely the way in which my understanding differs from the acquisitionist sociocultural one.

Now, of course, there are many different theorists to be counted among the acquisitionist sociocultural ones and so variations certainly exist among them. I shall concentrate on delineating my point of view in relation to those claims which seem most similar to mine, namely activity theoretical views emphasizing the tool-mediation of knowledge (Hedegaard, 1995; Säljö, 2000; Vygotsky, 1978; Wertsch, 1998), the corresponding distribution of cognition in action across tools and people (Hutchins, 1993, 1995; Hutchins & Klausen, 1996; Pea, 1993; Perkins, 1993), the direct perception of tools’ affordances and their integration as functional organs (Kaptelinin, 1996), and the existence of sub-conscious (tacit) operations which realize the actions we undertake in the course of our activities (Leontʹev, 1978). Other claims such as the overarching significance of language (Bakhtin, 1981) and the inherent dialogic nature of understanding (Bakhtin, 1981; Dawes & Wegerif, 2004; Dysthe, 2001; Wegerif, 2007) are further from my position, given my analysis of knowledge in practice as significantly involving tacit dimensions. I agree to the general sociocultural point that language is mediational and partly constitutive of activities at least at the higher analytical levels, but the amplification of this point into these more radical claims to my mind places too large an emphasis on what we say as compared to what (else) we do. Similar to the critique which I in Article 5 present of the English-speaking world’s Wittgenstein reception, one might say that proponents of these more radical claims tend to understand activity as necessarily linguistic activity – discourse – and thus overlook the significance of our actually physically acting in the world. As I put it in Article 8, whilst discussing social practice theorists’ (i.e. sociocultural views of both the acquisitionist and the participationist kinds) analysis and design of ICT-mediated learning, there is a tendency to forget the practice side of social practice theories, or – in this context – the activity side of activity theory. Marx’ original point that our understanding is founded on the material organization of how we live and produce our lives is given a too intellectualist rendering, one might say.

In contrast to this intellectualist rendering, Vygotsky, whose project it was to develop a Marxian psychology, and who is one of the ‘founding fathers’ of activity theory, actually made a point of not equating what he calls ‘external activity’ with ‘internal activity’, nor construing language as a tool on a par with physical tools (Vygotsky, 1978, pp. 54-55). In his own words:

“A most essential difference between sign and tool… is the different ways that they orient human behavior. The tool’s function is to serve as the conductor of human influence on the object of activity; it is externally oriented; it must lead to changes in objects… The sign, on the other hand, changes nothing in the object of a psychological operation. It is a means of internal activity aimed at mastering oneself; the sign is internally oriented.”(Vygotsky, 1978, p. 55)

In what follows, he goes on to stress that the external and internal activities are linked, both phylogenetically and ontogenetically. Mastering one’s behavior is a way to effect the mastering of nature; mastering nature is a way to change the conditions for human behavior and thus – in line with the general Marxist view – a way to change human nature, i.e. a way to master behavior. “Higher psychological function”, he asserts, combines tool and sign in psychological activity. Still the fact that he emphasizes the concept of ‘mediated activity’ as generic to understanding both tool- and sign-use as two different processes shows that he does not view practice first and foremost as ‘discourse’ nor see activity as constituted solely by language.

However, Vygotsky’s formulations are problematic in another respect. The very distinction between ‘internal’ and ‘external’ activities reinstates as primary the subject-object distinction which I have argued with the phenomenological tradition from Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty is a secondary one, posited in a withdrawal from our primordial being-in-the-world. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given that his aim was to construct a Marxian psychology, Vygotsky focuses on psychological functions, especially conscious ones, and how they come into being in our interaction with other people and the world. This focus is carried over in much of the activity theoretical literature. In consequence, even though the activity theoretical line of thinking takes its outset in the non-dualist, relationalist view discussed above, according to which person, activity, and world are mutually constitutive, its more specific analyses accord significance to consciousness and conscious mental activities over actual bodily doings and being-in-the-world. In this respect, the activity theoretical tradition shares Cartesian roots with cognitive and constructivist thinkers such as the ones mentioned above (Anderson et al., 1996; Carey, 2009; Cress & Kimmerle, 2008; Glasersfeld, 1995; Mayer, 2001, 2004; Mayer & Massa, 2003; Piaget, 1950; von Glasersfeld, 2001), and takes conscious mental activity as fundamental to understanding action, even if this mental activity is understood to be framed and get meaning from the sociocultural activities in which it is located.

This trend of understanding and – in my opinion – overly emphasizing consciousness as ‘internal ongoings’ is present in e.g. Kaptelinin’s discussion of the importance of an “internal plane of actions” which “refers to the human ability to perform manipulations with an internal representation of external objects before starting actions with these objects in reality” (Kaptelinin, 1996, p. 51); in Nardi’s explicit stress on motive and consciousness as what distinguishes humans from things (Nardi, 1996, p. 13); in Kuuti’s claim that actions are typically planned in advance in consciousness with the use of a model (Kuuti, 1996, p. 31); in Bærentsen & Trettvik’s emphasis on consciousness in learning to ‘directly perceive’ affordances (Bærentsen & Trettvik, 2002) and of course in the whole discussion from Vygotsky and onwards of the development of higher psychological functions as an internalization of interpersonal processes (with the development of thought as ‘internal speech’ from external speech as a prime example) (Vygotsky, 1978). It is also present in Leont’ev’s distinction of three levels of activity: the activity itself, understood as the meaningful pursuit of an object (the motive), the individual actions which realize the activity, and the operations which realize the actions. Leont’ev claims that we need not be fully aware of the motive and will not be consciously aware of the operations. This is, however, not because we are acting in immediate attunement to the demands of the situation (as I with Merleau-Ponty and Dreyfus would hold). Rather, in line with other Cartesian inspired views of the non-conscious, motive and operations are thought to work at sub-conscious levels ‘inside the agent’. Furthermore, consciousness is the outset: operations are learned as actions and ‘sink into’ automatization at a sub-conscious level where they are carried out in the same way as when they were conscious, now just ‘unconsciously’. They may also be brought back into consciousness for inspection or change, if need be (Kuuti, 1996; Leontʹev, 1978). As Dreyfus has argued, claiming that former conscious actions are carried out ‘automatically’ in the same way as before once one can perform them without awareness is like supposing that one still uses training wheels (now just invisible ones) when riding a bike seemingly without them, because one used them whilst learning to ride the bike (Dreyfus, 2001b).

My objection to this trend within activity theory is that it does not realize the full implications of taking one’s outset in the person-in-the-world, namely that one must analyze the person there, i.e. as embodied being, rather than perform the traditional Cartesian split of body and mind (external and internal) anew, after having noted the cultural meaning permeating both. As foreshadowed, this objection corresponds to the point at which my approach reconciles-whilst-challenging the participationist and acquisitionist strands. This is so, because my further analysis of the person there leads me to claim that knowledge as a style of being opens the world to the person ontologically and epistemologically, in stark contrast to the activity theorists’ acquisitionist focus on mental representation of actions and goals.

Now, some activity theoretical thinkers do seem to carry forth the implications of the outset of person-in-world. In particular, proponents of ‘distributed cognition’ appear to stick to analyzing the person there. Hutchins’ description of the navigation of a large sea vessel into port for instance makes a clear case for the need of a system’s view of the navigational process (Hutchins, 1993, 1995). Several people placed with different instruments at different locations on the ship are((Or were at the time of Hutchins’ investigation. The procedures have presumably changed radically with the advent of GPS instruments.))[29] necessary for the activity to succeed. Nonetheless, the necessity is functional: one person can simply not undertake all actions at once. Hutchins does stress that understanding what goes on in individual learning of a given task cannot be understood before the whole “dynamic system” (Hutchins, 1995, p. 289) of which the individual is part is understood. He further claims that he aims to “partially dissolve the inside/outside boundary” (p. 288) and emphasizes that structure to coordinate action may be implemented in the arrangement of external media (p. 316). Still, his more concrete descriptions of the cognitive activity involved actually appear rather focused on mental activities. In speaking of individual cognition, he repeatedly uses the phrase “internal structures” (p. 289) and “internal representations” (p. 288), even if he maintains that the identification hereof is functional, from the part such structures play in the whole dynamic system. Likewise, he describes the usage of a map in a way which seems to indicate a ‘communication’ taking place ‘inside’ the individual between what she sees in the world and what is there on the map:

“The task of reconciling a map to the surrounding territory has as subparts the parsing of two rich visual scenes (the chart and the world) and then establishing a set of correspondences between them on the basis of a complicated set of conventions for the depiction of geographic and cultural features on maps. As performed by an individual, it requires very high bandwidth communication among the representations of the two visual scenes.” (Hutchins, 1995, p. 285)

A Merleau-Pontian-Dreyfusian description of the same activity would instead focus on how the representational conventions of map writings were incorporated into the agent’s bodily take on the world so that she at once could act on the map’s features in viewing the surroundings. Or as I would put it: Such conventions are incorporated into the experienced map-reader’s action-oriented perspective so that map and surroundings appear to her as already coordinated. She sees the surroundings in the map directly and vice versa and has no need of coordinating representations.

Hutchins thus, upon closer inspection, does not appear to quite take the ‘embodied-person-in-the-world’ stance that one might expect, given that he is a prime representative of “distributed cognition”. Similar considerations go for other proponents of distributed cognition. Perkins’ analysis of the person-plus-surround as the compound system for thinking and learning builds on a view of thinking as ‘information-processing’ and actually provides a rather mentalist representation of the person side of the person-plus. In analyzing the person-plus of an engineer performing a task, Perkins gives several different examples of the ‘plus’-side (books, formulas, drawings, databases, calculators, computers etc.), but the person-side is only exemplified with mental processes and states such as “rich technical repertoire in long-term memory” and “mental representations” (Perkins, 1993). One is left with the picture of cognition as the workings of a mental entity which can utilize information from artefacts in the environment. The person-plus, one is inclined to say, is in point of fact just a mind-plus.

Likewise, though Pea argues that “intelligence is accomplished rather than possessed” (Pea, 1993, p. 50), he explains the individual’s engagement in activity with reference to Norman’s model (Norman, 1988/2002)((Pea refers to the first edition of the book, published under the name The psychology of everyday things in 1988.)) of the structure of activity, which is decisively mentalistic (with activity explained through 7 stages of mental processes). Pea indicates that he thinks Norman’s model presupposes “commitment to greater articulateness and mental representation” (p. 54) than our activities normally have. Still, he concludes the description of what he claims to be a Heideggerian example of activity resulting from “habitual desire” with noting that here “the seven stages of action are cycled with minimal notice” (p. 56). That is, the assumption is the mentalistic one that the stages are cycled, even if there is no indication in the activity itself thereof. Notably, Pea describes the example as one in which the person “merely repeats a familiar course of action”. In conjunction with the former quote, this indicates that he views such courses of action as routinized procedures which had one’s attention whilst one learned them. This is – contrary to what he claims – very far from being the Heideggerian thesis that we are always already embedded in a meaningful world where we know how to act. Finally, Pea’s explanation of the intelligence residing in tools is that they are “carriers of previous reasoning” (p. 53) in that “they represent some individual’s or some community’s decision that the means thus offered should be reified, made stable, as a quasi-permanent form, for use for others.” (ibid.) Here, too, he appears to prioritize conscious goal-directed behavior as the prime characteristic of intelligence and intelligent action.

Summing up, there is in the activity-theoretical approach in general a tendency to overlook the significance of the body in our engagement in the world, despite the role accorded to tool use as mediator of our understanding of the world.((Exceptions to this tendency exist. One such exception is Wertsch’ book Mind in Action which, as the title indeed would suggest, is very much in line with my point of view. He argues that the primary unit of analysis should be ‘mediated action’ and discusses the skill of pole vaulting as one paradigm instance hereof, alongside an ‘intellectual’ skill such as multiplication, which is more typically considered by activity theorists. Though he does not as such provide an analysis of the body in action, and in particular does not discuss its significance for intentionality and understanding, he certainly does not succumb to providing a mentalist explanation of mediated action. On the contrary, he explicitly criticizes the term ‘internalization’ because it “entails a kind of opposition, between external and internal processes, that all too easily leads to… mind-body dualism” (Wertsch, 1998, p. 48) and asserts that “many, and perhaps most, forms of mediated action never “progress” toward being carried out on an internal plane… It is unclear what it could mean to talk about carrying out this form of mediated action [pole vaulting] on an internal plane.” (p. 50). I fully agree with him as also with his suggested alternative terminology of “mastering the use of a cultural tool” (p. 51).)) To a large extent, this mediation is construed as trigger point and content provider for the development of conscious representations of the world, rather than as an aspect in the development of an understanding of the situation at the bodily level itself in the form of an actionable attunement to it. Correspondingly, though the concept of affordance has been given some attention within activity theory (e.g. Bærentsen & Trettvik, 2002; Hedestig & Kaptelinin, 2009), focus has been on the perception of affordances as part of conscious goal-directed action. For the same reason, the activity theoretical understanding of the incorporation of tools into the body as the outset for perception and action in the world typically does not get beyond Leont’ev’s concept of ‘functional organs’ (Leontʹev, 1981) which are deliberately put on to effect a specific end, such as glasses or hearing-aids. In Kaptelinin’s words “Functional organs are functionally integrated, goal-oriented configurations of internal [e.g. the individual’s own eyes and brain processing of sight] and external [e.g. the glasses] resources” (Kaptelinin, 1996, p. 50). Or as he writes in a recent book, co-authored with Nardi: “One implication of the notion of functional organs is that distribution of activities between the mind and artifacts is always functional.” (Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2012, p. 28). The neglect of the significance of the body is obvious in this quote where Kaptelinin and Nardi, quite analogous to Perkins’ understanding of distributed cognition above, construe the distribution of sensing of the ‘person-plus-artefact’ as accomplished solely by a ‘mind-plus-artefact’. These quotes contrast with my Merleau-Pontian inspired analysis of our immediate bodily attunement to the situation beneath and as background for conscious action; of the way tools may be integrated into this background ‘take’ on the world, and of how we may act on the affordances of the environment as part of the attuning, without awareness thereof.

One final point: The preceding discussion of differences between my view and activity theoretical approaches should not be interpreted as involving the claim that we never act consciously or goal-directly. The fact that most people, if stopped to ask what they are doing, will provide an answer which makes reference to an intention shows clearly that most of the time at least part of what we are doing may be rationalized as having a goal. My contention here is only the following: First, that the activity theorists’ focus on the level of conscious, goal-directed behavior neglects the vital background bodily attunement on which such conscious, goal-directed action takes place. Second, that quite a lot of our activity phenomenologically has the character of everyday, familiar ‘going about our business’ with no explicit goal awareness, though it may be rationalized as ‘goal-directed’ if need be. Planned, modelled action is not nearly as widespread as Kaptelinin and Kuuti would have us believe (Kaptelinin, 1996; Kuuti, 1996). This was Ryle’s point in the quotation above in section 2.2. that ” “to perform intelligently is to do one thing and not two things.” (Ryle, 1949, p. 40).

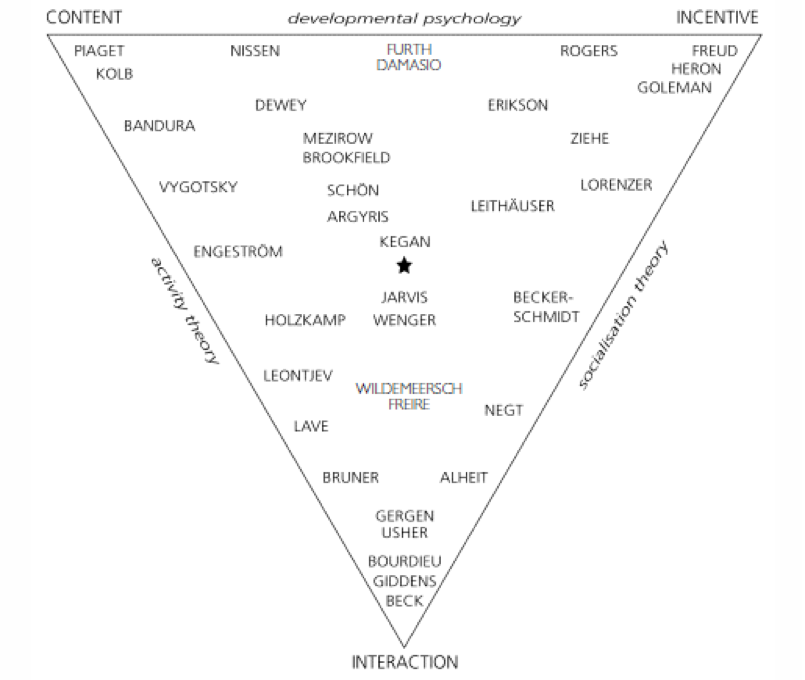

This brings me to the last stage of the clarification-by-contrast with other views within the learning theoretical field, namely the characterization of my approach in relation to other individualist positions. To this end, Illeris’ schematization of the field as drawn out between the three dimensions of content, incentive, and interaction is helpful((In his first, Danish, text, Illeris identifies the dimensions as cognition, psychodynamics, and societal aspects.)) (Illeris, 1999, 2007, 2009), cf. figure 2.

Illeris himself claims to view learning as an integrated process which always involves all three dimensions. He builds his view through discussion and integration of a number of theorists concerned in different ways with the development of human and societal aspects related to these dimensions. Characterizing all theorists within the triangle as concerned with ‘learning’ or even as positions within a “tension field of learning” as Illeris does (Illeris, 2007, p. 256ff) is somewhat distorted in my opinion, though. Marx, for instance, even in his early writings to which Illeris alludes, was first and foremost concerned with pinpointing the ontological co-constitution of material world and the being of humans. Giddens and Beck similarly are hardly ‘learning theorists’, even if their depictions of modernity and reflexivity have implications for understanding learning in modern day society. Portraying Freud’s psychoanalytical theory as concerned with learning appears a rather gross misrepresentation which is not diminished by the fact that Freudian considerations of ‘psychic energy’ inspired Furth to develop his theory of “knowledge as desire” (Furth, 1987). All theorists may have argued points which Illeris finds useful in the analysis of learning, but making them all fit into the categorization emerging out of Illeris’ line of inquiry not only distorts the issues they were concerned with but – in consequence – the actual contribution they may offer to learning theory. Marx, Giddens, and Beck for instance, are not theorists who only see the societal tip of the iceberg of learning whilst totally ignoring the dimensions of incentive and cognition. Their research questions are simply different ones, though tangentially relevant to learning.

Illeris situates his own view in “the focal point close to the centre of the figure” (Illeris, 2007, p. 259). This is unsurprising, bordering on tautology, given that the figure is constructed as a representation of his claim that all learning always involves the three dimensions. As I noted above, Illeris’ position is paradigmatic for acquisitionists’ understanding of the way knowledge issues relates to motivation, identity development and interaction with others: They relate as ‘factors’ which may influence and be influenced by each other, but which one can meaningfully draw apart and represent as factors or dimensions. A participationist such as Lave would presumably object to being placed on the left hand side of the triangle, as if she fully neglected issues of motivation, emotion and volition, and would argue that such ‘factors’ are not ‘factors’ at all, understood as mental traits or phenomena ‘inside’ the individual, which can be influenced by the interaction going on ‘outside’ of him. Illeris’ dimensions would not be dimensions to Lave; rather, the dynamic interactional system of which the individual is part would be a lens for understanding how individuals negotiate knowledge and incentive in and across situations. If viewed as a diagram of inspirational points for Illeris’ own position, however, the placements of theorists in the triangle appears reasonable. Given his outset in the assertion of the three dimensions, his categorization of the way different theorists contribute to the elucidation of each of these is illuminating, as is his placement of the theorists relative to each other. Weighed on his scale of three interacting dimensions, one might put it figuratively, each theorist comes out as a unique combination of weights. For illustrative purposes, I shall weigh my own view on his scale as well and thereby locate myself relative to other learning theorists, as construed from the individualist acquisitionist position. I do this, however, with the caveat that Illeris’ schematization fundamentally accepts the Cartesian split between inner subject and outer world which I have been arguing against with Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty.

Given that my position originates in the epistemological concern with how ‘knowledge in practice’ is developed, my research questions are definitely to the left side of Illeris’ triangle. My explication of knowledge as a style of being which opens the world to one ontologically as well as epistemologically, and my emphasis on knowledge as taking on form and content from the concrete situation, including some degree of social negotiation of what knowledge is, further locates my view somewhere down the line towards the societal dimension. I am – in line with the objection I attributed to Lave – somewhat skeptical about distinguishing incentive as a separate dimension from content and interaction: It seems obvious to me that the former will have a content side and to some extent be constituted by negotiation with others about the significance of the content, though I do not believe it to be fully determined by this negotiation. Going along with Illeris’ schematization, nonetheless, and taking my reservations concerning the incentive dimension as an indicator that my view would certainly not be weighted to the right of the triangle, but on the other hand as signifying that I include emotional and motivational phenomena among the ‘situational demands’ which actualize knowledge in practice, I locate my view at around the spot where Illeris’ has placed Schön and Argyris. Illeris says of his placement of these two theorists:

“…also in this area are Argyris and Schön, who are a little difficult to fit in. With their single- and double-loop model, they have apparently an individual psychological approach, which should place them in the upper part of the field, but, on the other hand, they relate themselves to the domain of organizational learning, which is a social area. Moreover, they primarily deal with the content side of learning but do not avoid emotional references. Thus they must be placed rather close to the centre of the field, but somewhat in the direction of the cognitive pole.”(Illeris, 2007, p. 258)

I think most of these arguments, mutatis mutandis, apply to my position, too, from the point of view of Illeris’ schematization. I am not taken up with the domain of organizational learning as Argyris and Schön are, but I think this is ‘evened out’ by my insistence on keeping the focus on the “person-in-the-world”. This contrasts with their central, ‘inwardly’ psychologically centered, claim that people’s actions are decided by ‘theories-in-use’ which they employ ‘implicitly’ or ‘unconsciously’, often quite at variance with what they will explicitly say (and think) are reasons for their actions as articulated in their ‘espoused theories’ (Argyris & Schön, 1996). My rejection of Vygotsky’s notion of ‘internalization’ as a reintroduction of the Cartesian internal-external divide and my resulting doubts of his concern with consciousness certainly places me further towards the societal dimension than him. Conversely, Engeström’s development of activity theory into a theory of communities’ “horizontal or sideways learning” (Engeström, 2001, p. 153) by “expansive learning” (cf. also Engeström, 1987) explicitly takes the collective of the ‘activity system’ as its outset which places him further down the societal line than me in Illeris’ schematization. Incidentally, in the case of Engeström, too, I find Illeris’ contention that he is not concerned with the incentive side surprising: Engeström’s other main source of inspiration in addition to activity theory is Bateson and in particular Bateson’s notion of double bind situations resulting from contradictory contextual demands. As described by Bateson, a double bind situation is extremely stressful – “expectably schizophrenogenic” is the wording he uses (Bateson, 1972, p. 297). Engeström points out that “Such pressures can lead to Learning III where a person or a group begins to radically question the sense and meaning of the context and to construct a wider alternative context.”(Engeström, 2001, p. 138) Though he characterizes Bateson’s idea of the learning which may result of the double bind situation as “a provocative proposal, not an elaborated theory” (p. 139), I find it beyond doubt that the “pressures” he mentions belong to the domain of incentives. Engeström may primarily be taken up with transformations in conceptualizations and practices, i.e. with the ‘content dimension’, but he posits ‘double bind’ situations as the drive which initiates such transformations. To me, this further indicates the problem of postulating the domain of the incentive as a dimension of its own.

There are other placements of theorists made by Illeris which could be contested. Jarvis, for instance, arguably should be placed even closer to the middle or on the other side of it, given the person-centered view of learning which he presents in his first book of the trilogy Lifelong Learning and the Learning Society. The next two books add further perspectives (a sociological one and a visionary one concerned with the learning society as a project of humanity itself), but do not radically change his conception of learning as a “process of transforming the experiences that we have” (Jarvis, 2007, p. 2). Actually, though Jarvis explicitly stresses the ’person-in-the-world’ as the entity that learns (Jarvis, 2006, p. 13ff) and counts “pre-conscious learning” (p. 28) as one of the ways in which we can learn; still, his description of the learning process appears quite focused on “sensations” (p. 20ff) and “experiences”(p. 27ff) ‘inside the mind’ of the individual. Thus, he describes learning as initiating in a “state of disjuncture” where we have “ a sense of unknowing” which leads us to raise questions (sometimes only implicitly), the answers to which – once found – have to be “commit[ted]to memory” for learning to occur (p. 19). In comparison with theorists such as Vygotsky and Engeström, he should therefore in my opinion should be placed quite close to the former on the societal dimension, instead of even further down the societal dimension than the latter. He definitely strikes me as accepting the Cartesian subject-object split to a much higher degree than Wenger whom he is placed very close to. Arguably, he should be placed very close to Dewey (the placement of whom I concur with) whose understanding of sensation and experience (Dewey, 1933, 1938, 1960) lies at the heart of Jarvis’ description of learning. Certainly, Jarvis appears more cognitively/individualist focused than me and I would see myself placed further down the societal line than him.

Similarly, Alheit’s biographical research (Alheit, 1994, 1995, 2009) is focused on the individual’s unique life course so I find it somewhat incomprehensible that his theory is placed so close the societal pole: Though the life course is understood to take place in an interaction between individual subjectivity and societal conditions; still, when Engeström with his focus on the evolvement of collective practice is placed so high up the societal line, it seems hard to defend a placement of Alheit’s position so far down. Perhaps, again, the problem is the treatment of incentive as a dimension of its own: Though one could argue that emotions may take different societal forms and that different cultures may value, nurture, and pursue different kinds of incentives, such ‘societal mediation’ would be a mediation of the content domain of incentive, not of incentive itself. Thus, it would belong within the content dimension. On this view, the incentive as incentive would necessarily be experienced by the individual, and therefore the societal line on the right side of the triangle is not at all comparable with the societal line on the left side.

With these considerations I shall end this section’s situating of my view within the learning theoretical landscape. Though I – as indicated – have some reservations about Illeris’ schematization as well as about his placement of individual theorists within it, overall I think his diagram serves to locate my position from an individualist acquisitionist perspective. Viewed from here, my position shows itself as taken up more with the content side of learning than with the incentive side, and with a societal strand integrated with my individualist outset. Inspirations for my view come mostly from the left-middle part of Illeris’ diagram. I would demarcate my stance as at variance with theorists at both individualist poles. I accept the general Marxian view of person-in-the-world at the societal pole, but do so from the standpoint of the individual. This placement of my view accords with the demarcation of my view which I presented in the first two stages of this section, where I argued that my position reconciles-by-challenging the acquisitionist-participationist distinction and provides an alternative to sociocultural acquisitionists’ tendency to reintroduce the Cartesian split between subject and object.